Medical Design Briefs - October 2025

Micronewton Scale Biotribometer Research of Low Friction Aqueous Gels, Cells, and Tissues

By Jim McMahon Minus K Technology

When measuring qualities of interacting surfaces in relative motion, such as the coefficient of friction, friction force, adhesion, wear volume, lubrication, and deformation, the tribometer is the instrument of choice. Typically, tribometers are used to characterize rigid substrates utilizing a rigid probe, which measures friction forces through deflections of the cantilever supporting the probe.

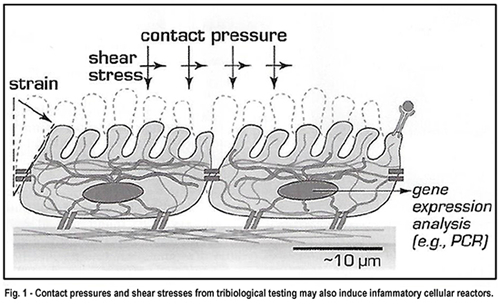

But characterizing soft surfaces such as cells or other delicate tissues with tribometry presents a significant challenge. Hard probes used to test such surfaces damage the cells and tissues. Contact pressures and shear stresses from tribological testing may also induce inflammatory cellular reactions (see Figure 1).

"Soft implant materials increasingly being used in biomedicine for contact lenses, clamps, catheters and soft tissue prostheses present significant experimental challenges during surface characterization with tribometry," says Prof. Angela Pitenis, Interfacial Engineering Lab, University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB). "Over the last two years my lab has been investigating microscale contact areas and forces between aqueous gels and cells. We want to understand how cells respond to mechanical stimulation caused by soft implants."

"The need to examine biocompatibility of these implant materials has introduced opportunities to develop specialized instrumentation for tribological studies of these low friction aqueous gels, cells and tissues," says Pitenis. "So we developed our own custom instruments with the ability to observe and monitor changes in the contact area within the deformations of these soft materials."

"The need to examine biocompatibility of these implant materials has introduced opportunities to develop specialized instrumentation for tribological studies of these low friction aqueous gels, cells and tissues," says Pitenis. "So we developed our own custom instruments with the ability to observe and monitor changes in the contact area within the deformations of these soft materials."

"We design and fabricate precise in situ instrumentation that interrogates microscopic contacts of cells under microscale forces (25 mN to over 1,000 mN)," adds Pitenis. "A wide variety of cell and tissue types, along with soft biocompatible materials are frequently used in combination to create model interfaces from which to study fundamental mechanisms associated with biological responses to contact and shear."

Biotribology Research

Key instrumentation developed by the lab includes an in situ biotribometer that can directly measure dynamic interactions of biological interfaces during contact and sliding. The design enables microscale force measurements during non-destructive indentation and friction studies of biological materials over large contact areas and sliding distances using spherical shell high water content aqueous gel probes. The biotribometer is designed with increased sensitivity in the friction force direction to reduce uncertainties associated with measurements of low-friction aqueous gels, cells, and tissues (see Figure 2).

"The low elastic modulus of cells and the relative thinness and fragility of cell monolayers present challenges to multi cell contact testing," explains Pitenis "Because of the relative stiffness of most synthetic gels and silicones, as compared to cells and tissues, matching contact pressures has been a concern. However recent designs of highly compliant probes by our lab allow for small radius of curvature, finite contact width, and contact pressure that can be tuned by altering the probe thickness rather than the material properties."

"The low elastic modulus of cells and the relative thinness and fragility of cell monolayers present challenges to multi cell contact testing," explains Pitenis "Because of the relative stiffness of most synthetic gels and silicones, as compared to cells and tissues, matching contact pressures has been a concern. However recent designs of highly compliant probes by our lab allow for small radius of curvature, finite contact width, and contact pressure that can be tuned by altering the probe thickness rather than the material properties."

The lab characterizes the material used to make the probes with indentation measurements well before the probes are applied in biotribological experiments. The cantilevers used to support the probes are so soft that they can measure one micronewton of applied force.

Mounting the biotribometer onto an inverted microscope allows for direct imaging of the contact in situ. Monitoring the responses of cells with fluorescence microscopy allows for a wide variety of fluorescent stains, dyes and reporters to be quantitatively imaged in situ, and dynamically enables mechanistic studies of cellular responses to direct contact shear.

"We measure a number of readouts," says Pitenis. "Fluorescent dyes can be used to visualize early markers of inflammation or cell death in cell layers in response to mechanical stimulation."

"Unlike tribological testing with reference materials, biotribological samples have significant variables from batch to batch, patient factors and history of handling and preparation," says Pitenis. "A wide variety of cell and tissue types, along with soft biocompatible materials are frequently used in combination to create model interfaces to study fundamental mechanisms associated with biological responses to contact and shear."

The lab has also devised unique containers for growing and managing cells during biotribometry to keep cell groups separated when being probed by the biotribometer. Typically, cells being probed secrete molecules, inflammatory markers, into the media, which are carried through to other cells in the media which are not being probed. To keep these groups separated, and inhibit cross-cell contamination, the lab has devised containers to separate out the cell groups.

Vibration Isolation

The lab's biotribology research is conducted on top of an air-cushioned optical table with 10 N and 25 N stages to provide passive damping. Because the lab's research often measures very low friction coefficients of approximately 0.01 and below, any vibrations from the environment could interrupt measurements.

"We measure forces on the order of micronewtons," says Pitenis. "Vibration isolation is critical to our research. Footfall from someone walking by, the closing of doors -- even with the optical table, these vibrations will still be measured."

Consequently, the lab has added another layer of vibration isolation designed to more thoroughly cancel out low-frequency horizontal-direction vibrations coming up through the floor.

"We selected a negative-stiffness vibration isolator from Minus K Technology," says Pitenis. "It supports the biotribometer and the specimen container. The isolator is positioned on the breadboard. The negative-stiffness isolator is working fantastically," she says. "It is an excellent design choice for our research."

Negative-Stiffness Vibration isolation

Negative-stiffness vibration isolation was developed by Minus K Technology, an OEM supplier to manufacturers of scanning probe microscopes, micro-hardness testers, and other vibration-sensitive instruments and equipment. The company's isolators are used by more than 300 universities and government laboratories in 52 countries.

These vibration isolators are compact and do not require electricity or compressed air, which enables sensitive instruments to be located wherever they are needed. There are no motors, pumps, or chambers, and no maintenance is required because there is nothing to wear out. They operate purely in a passive mechanical mode.

Negative-stiffness isolators achieve a high level of isolation in multiple directions. These isolators have the flexibility of custom tailoring resonant frequencies to 0.5 Hz vertically and horizontally (with some versions at 1.5 Hz horizontally; see Figure 3).

"Vertical-motion isolation is provided by a stiff spring that supports a weight load, combined with a negative-stiffness mechanism," says Dr. David Platus, inventor of negative-stiffness isolators, and president and founder of Minus K Technology. "The net vertical stiffness is made very low without affecting the static load-supporting capability of the spring. Beam-columns connected in series with the vertical-motion isolator provide horizontal motion isolation. A beam-column behaves as a spring combined with a negative-stiffness mechanism. The result is a compact passive isolator capable of very low vertical and horizontal natural frequencies and high internal structural frequencies."

Negative-stiffness isolators deliver high performance, as measured by a transmissibility curve. Vibration transmissibility is a measure of the vibrations that are transmitted through the isolator relative to the input vibrations. Negative-stiffness isolators, when adjusted to 0.5 Hz, achieve approximately 93 percent isolation efficiency at 2 Hz; 99 percent at 5 Hz; and 99.7 percent at 10 Hz.

Possibilities

"The research being done at the UOSB Interfacial Engineering Lab opens the door for the exploration of entirely new engineering approaches and designs of soft implants that control surface shear stresses and manage inflammation and cell death through new surface chemistries, material properties, and improved interfacial interactions," says Pitenis. "And a critical support to the success of this research is negative-stiffness vibration isolation."

This article was written by Jim McMahon, who writes on industrial, manufacturing, and technology issues. For more information on negative-stiffness isolators, contact Steve Varma, Operations Manager, Minus K Technology, Inc. at request@minusk.com or visit www.minusk.com.

|